Editor’s Note: Peter Pashkov has a PhD in Theology, and serves as a Senior Lecturer at St. Tikhon’s University in Moscow and Editor at the “Orthodox Encyclopedia“. This article is contextualized in a debate with a Protestant on the question of icon veneration in Christian antiquity. In light of many recent debates in the English world concerning the genuine antiquity of iconodulia in the Christian world, especially in light of the claims of the Second Council of Constantinople, this article provides the debate with a wealth of knowledge and resources to support the Orthodox position. This article was translated from the original Russian by the editor, with revisions by the author to capture the essence and key elements of the debate in the English language.

It is established that the Seventh Ecumenical Council prescribes that Orthodox Christians should venerate icons: “To those who do not receive with love the holy and venerable icons, Anathema! To those who call the sacred icons idols, Anathema! To those who say that Christians turn to icons as to gods, Anathema!”1 As such, Orthodox Christians explain their veneration of sacred images (or icons) by saying that by honoring the images of Christ and his saints, they express their reverence for those depicted: “because the honor given to the icon is transferred to its prototype, and the one who venerates the icon venerates the person (hypostasis) depicted on it.”2 A conscious refusal to venerate sacred images (that is, aniconism) and perceiving them as idols places a Christian outside the bounds of Orthodoxy (just as Roman Catholicism). Our opponents assert that by this standard, early Christianity falls outside the bounds of Orthodoxy (understood as the “Church after the ninth century”). This accusation seems serious and, at first glance, even justified. Nevertheless, there is much to ponder here, and the final conclusions would seem to be far from being so obvious.

I. Icon Veneration in the Fourth Century

First, it is important to note that there is practically no room for doubt about the widespread veneration of sacred images in the “Constantinian” era, i.e., after the Edict of Milan in 313 and the Council of Nicaea in 325. This practice spread very quickly and not only in the Greco-Roman areas of the Christian world. Here are a few examples:

1. One of the often mentioned pieces of evidence is St. Gregory of Nyssa’s remarkable description of the icon of Martyr Theodore Tyron, placed above his relics. As a reminder:

“Should a person come to a place similar to our assembly today where the memory of the just and the rest of the saints is present, first consider this house’s great dignity to which souls are lead. God’s temple is brightly adorned with magnificence and is embellished with decorations, pictures of animals which masons have fashioned with delicate silver figures. It exhibits images of flowers made in the likeness of the martyr’s virtues, his struggles, sufferings, the various savage actions of tyrants, assaults, that fiery furnace, the athlete’s blessed consummation and the human form of Christ presiding over all these events. They are like a book skillfully interpreting by means of colors which express the martyr’s struggles and glorify the temple with resplendent beauty. The pictures located on the walls are eloquent by their silence and offer significant testimony… Should a person have… permission to touch the relics, this experience is a highly valued prize… In this way one implores the martyr who intercedes on our behalf and is an attendant of God for imparting those favors and blessings which people seek.”3

In fact, St. Gregory describes a quite traditional Orthodox icon with scenes depicting the feats of Martyr Theodore, inscribed on the wall above the relics of the martyr. The “human image” of Christ is also placed on the “icon.” Further, the saint speaks of prayer before the relics (and, accordingly, the icon), understood as “imploring the martyr who intercede on our behalf” It is difficult to imagine a picture more obviously coinciding with the modern practice of Orthodox piety and church life.

2. To avoid burdening the reader, we will not overly multiply examples of veneration of sacred images in the fourth century. However, we must point to a complex of testimonies related to the image of the Saviour kept in Edessa. Obviously, in the context of the controversy, we cannot appeal to the stories of the Mandylion, sent to King Abgar of Osroene, as evidence of the existence of sacred images in the first century. Nonetheless, at the end of the fourth century, the image of the face of Christ was already definitely in Edessa and served as an object of veneration. We know that in 384, when the Gallic pilgrim Egeria visited Edessa, the relics of the Apostle Thomas and the “letter of Christ to King Abgar” (apocryphal, of course) were the objects of veneration in this city, while the image is not mentioned by Egeria among the most important relics.4 But already in the “Teaching of Addai,” a Syriac early Christian text from the late fourth century, the story of the image of Christ is present, although the image is not called “not made by hands” (the legend claims that the icon was created by King Abgar’s court painter):

“When Hannan, the archivist, saw that Jesus had spoken to him in this way, since he was the king’s painter, he took and painted an image of Jesus with the best colors and brought it with him to King Abgar, his lord. When King Abgar saw this image, he received it with great joy and placed it with great honor in one of the rooms of his palace. And Hannan the archivist conveyed to him all that he had heard from Jesus, for he had written down his words.”5

What can we understand from this? That at the end of the fourth century (specifically, after 384), there was a sacred image of Christ in Edessa. It was ancient—at least, it could not have been newly created, otherwise, nobody would consider it a relic of the earthly life of the Savior. It was not considered “not made by hands” but was treated with “great honor,” i.e., it was venerated.

_______

At the end of the 4th century, an ancient sacred image of Christ was already venerated in Edessa.

______

3. To demonstrate the remarkable unanimity of the Eastern and Western Christian world with respect to the veneration of sacred images, let us pay attention to the account of Egeria, whom we have already mentioned, about the veneration of the Holy Cross in Jerusalem:

“Then a chair is placed for the bishop in Golgotha2 behind the Cross, which is now standing;3 the bishop duly takes his seat in the chair, and a table covered with a linen cloth is placed before him; the deacons stand round the table, and a silver-gilt casket is brought in which is the holy wood of the Cross. The casket is opened and (the wood) is taken out, and both the wood of the Cross and the title1 are placed upon the table. Now, when it has been put upon the table, the bishop, as he sits, holds the extremities of the sacred wood firmly in his hands, while the deacons who stand around guard it. It is guarded thus because the custom is that the people, both faithful and catechumens, come one by one and, bowing down at the table, kiss the sacred wood and pass through. […] And as all the people pass by one by one, all bowing themselves, they touch the Cross and the title, first with their foreheads and then with their eyes; then they kiss the Cross and pass through, but none lays his hand upon it to touch it.”6

The scene described by Egeria directly parallels with what we can see in any modern Orthodox church when Christians approach a relic to kiss it. Even the kissing as a form of veneration is performed in the same way as today. Moreover, to Egeria, a pilgrim from Gaul, everything that is happening does not surprise or shock her. She does not find it necessary to further explain the phenomenon of kissing the Cross to her readers. In other words, for her, the sight of worshiping the Cross and kissing it is not some relic of paganism, not a peculiar Eastern custom, but something natural.

4. And even those texts from the 4th century, which our opponents perceive as favorable to their aniconic position, in fact, only confirm our conclusion. This primarily applies to the texts attributed to St. Epiphanius of Cyprus. We do not claim to resolve the issue of the authenticity of his “iconoclastic” writings. Even if some of them are indeed iconoclastic forgeries, most researchers acknowledge the authenticity of St. Epiphanius’s “Will,” as well as the Greek version of his letter to John of Jerusalem. But what do they tell us?

a. “When we were traveling to the holy place in Bethel to meet Your Honor there for joint [church] prayer, then, arriving in the village called Anavta, we noticed a burning lamp, and, upon inquiry, learned that there was a church in this place; and entering there to offer a prayer, we saw on the doors a painted veil on which was depicted something manlike and idol-like; and we were immediately told that this is an image of Christ or one of the saints, — this I do not remember; having examined [this veil], since I knew that when such things are in the church — this is an abomination, I tore it down.”7

Undoubtedly, this fragment speaks of St. Epiphanius’s rejection of sacred images. But on the other hand, we see that even in a small village, which is not particularly noteworthy, the altar veil (let us note, by the way, the fact of its presence) is sanctified with an image of Christ. Perhaps St. Epiphanius was an opponent of icons, but by the end of the 4th century, he was doomed to find them even in the most remote corners of the Christian world, and this is, perhaps, more important for our study than the fact of the Cypriot saint’s criticism of this practice.

b. From St. Epiphanius’s “Will”:

“Remember, beloved children, that icons should not be placed either in temples or in tombs where the saints are buried, but always keep God in your hearts, remembering Him; do not place icons in common houses either. For a Christian should not be carried away by the eyes and wanderings of the mind; therefore, let what pertains to God be written and depicted inside your hearts for all of you.”8

This is probably the most indisputable of the fragments attributed to St. Epiphanius concerning icons; there is no serious reason to doubt its authenticity. At the same time, several interesting features can be found here. Firstly, of course, the very fact of attempting to prohibit the installation of new icons (and not even remove existing ones, but only prohibit new ones) in temples, tombs, and houses only indicates that they were already there. Like modern Orthodox Christians, the Orthodox of the late 4th century kept icons at home and in temples and prayed before them (what other purpose would icons serve at home?).

_____

Like modern Orthodox Christians, the Christians of the late 4th century kept icons at home and in temples and prayed before them.

____

Aside from this, the motivation behind the removal of icons from churches is interesting. St. Epiphanius no longer says that icons are idols (unlike in his letter to John of Jerusalem) and does not consider them an “abomination.” His considerations are of an ascetic nature: icons captivate the gaze and are therefore bad. This can be compared to St. Augustine’s attitude toward church music — the Latin saint, as is well known, considered church singing dangerous for the soul because, captivated by the beauty of the melody, one could forget about the meaning of the hymns.9 Undoubtedly, such motivations are important and noble. But it is unlikely they can have dogmatic significance.

5. The hopelessness of the struggle against sacred images in the Constantinian era can be demonstrated by the example of the construction initiated by the first Christian emperor:

“In [Rome], at one time, Constantine Augustus built and adorned […] the Basilica of Constantine, to which he presented the following gifts: a ciborium made of chased silver, on the facade of which the Saviour is depicted sitting on a throne, 5 feet high and weighing 120 pounds, as well as 12 apostles, each weighing ninety pounds, 5 feet tall, and crowned with pure silver crowns; further, on the reverse side, facing the apse, the Saviour is also depicted sitting on a throne, 5 feet high, made of pure silver, weighing 140 pounds, and 4 silver angels.”10

Summing up the results of our observations, we can conclude that by the end of the 4th century, sacred images (primarily in the form of Cross depictions, but also as icons as we see them today) were widespread throughout the Christian world to a greater or lesser extent. The Cross was kissed, bowed before; icons were kept at home, painted on church curtains, and Christians prayed before them. Churches were decorated with statues of saints and Christ Himself. Even texts critical of these practices from that era only prove how widespread and deeply rooted icon veneration was in the 4th century. Once the Church was free and had the opportunity to build its places of worship and develop practices of piety without fear of persecution, icon veneration flourished. Perhaps this flourishing of iconography had some prerequisites in an earlier era?

II. Sacred Images in Judaism and Early Christianity

Here, we must make a small digression and quote an extensive passage from the work of Eliezer Lipa Sukenik, a prominent Israeli archaeologist:

“But the whole conception of the Jewish attitude towards pictorial representations of living beings <…> needs to be revised. The letter of Ex. 20: 4; Dt. 5: 8 admits formally of being constructed as a prohibition of all such representations, and there has always been a school in Jewry that has so construed it. But clearly the intention of the Lawgiver, whose language is here not juristically precise, was to qualify this verse by the following one, and only to prohibit the worshipping of images or the making of images for purposes of worship; and there has always been a less austere school in Jewry that has so understood it. Those who canonized the account of the ornaments of Solomon’s Temple, 1 K. 6-7; 2 Chr. 3-4, or of his throne, 2 Chr. 9-cherubim, bulls, and lions cannot have found anything in it to offend their religious feelings. Ezekiel’s vision of the restored Temple includes the faces of cherubim, lions, and men as decorative motifs, Ezek. 41: 18-20, and this fact did not stand in the way of the canonization of this book either.

It can be assumed that in calmer times, when a more tolerant tendency prevailed, while crises and persecutions triggered particularistic and rigourist reactions. […] The only rational explanation for the situation in ancient synagogues is that in Jewish history, the visual arts had their ups and downs: a period of greater leniency was followed by a reaction. The synagogues of Palestine provide us with particularly valuable testimony of both the tolerance that once prevailed there and the subsequent reaction against this tolerance. […] The only rational explanation of the situation found in the ancient synagogues is therefore that pictorial art had its ups and downs in Jewish history, a period of greater laxity being followed by a reaction; and the synagogues of Palestine afford us a peculiarly valuable evidence of both the latitude that at one time prevailed in that country and the later reaction against it. […] We may imagine, though we cannot prove, that the Palestinian authorities first set their faces against sculptures but still tolerated wall paintings and mosaics; then, with increasing persecution and misery, also vented their bitterness upon two-dimensional representations of animals and human beings. The first phase is attested, for example, by Capernaum, with its mutilated animal reliefs by the side of undamaged vegetable ones, and the second by the floor of ‘Ain Dûk, whose Zodiac was deliberately smashed whilst the accompanying inscriptions were spared. As we have seen, synagogues that were abandoned prior to a certain date, such as those of Jerash and Beth Alpha, escaped this fate. Regarding Chorazin, at which most of the figures have been preserved intact, we have an explicit statement by Eusebius and Jerome’ that it was already uninhabited at the time when they lived in Palestine; and the fourth century may therefore be taken as a terminus a quo for the reaction against sculpture. On the other hand, the Beth Alpha mosaic, with its Zodiac and seasons and its picture of the sacrifice of Isaac, was actually paved as late as the sixth century, and the latter date may be taken as the terminus a quo for the reaction against this genre of art.

The latter circumstance suggests that a contributing factor in the final banishment of human and animal motifs from the synagogues of Palestine may have been the influence of the iconoclastic movement that set in among the Monophysite Christians of the Near East at about this time and which has likewise left its traces in broken church mosaics; the conquest of the country by the Arabs, bearers of a religion unequivocally hostile to the representation of living beings, could of course only have intensified this environmental suggestion.” (Sukenik E. L. Ancient Synagogues in Palestine and Greece. L., 1934. P. 63).

___

The Concept of Jews’ Attitude Toward Pictorial Representations of Living Beings Needs Revision.

___

In other words, the traditional narrative of early Christian aniconism, based on the supposition that Christians inherited the aniconism of the Jewish religion, is simply incorrect. Intertestamental Judaism was not inherently hostile to the idea of sacred images, and Christians could not have adopted this idea from Judaism.

III. The Cross as a Sign of Christ

We have already established that even if “intertestamental” Judaism did not have a widespread practice of creating sacred images, it was, firstly, not inherently and fundamentally hostile to it, and secondly, it had the prerequisites for its emergence. As early as the 3rd century, Jews were making sacred images (see, for example, the Dura Europos synagogue). Sacred images also definitely existed among early Christians at that time (we will discuss this further). However, the mere presence of sacred images does not yet imply icon veneration, as icon veneration implies not only the existence of the icon but also its, well, veneration; “because the honor given to the icon is transferred to its prototype, and the one who venerates the icon venerates the hypostasis of the one depicted on it.”11

Can we speak of the veneration of sacred images that would correspond to this principle before the 4th century? As it happens, we can, although the first of such venerated images is not strictly speaking an icon. The primary form of Christian sacred image is the Cross, drawn, made of wood, or made in the form of a sign of the cross. Why can we speak of the veneration of the Cross as the primary form of icon veneration (or, more generally, as the veneration of a sacred image)?

To understand this, we need to deal with the concept of a “sign” (signum, σημεῖον). A sign, according to the now-classic definition of Y.M. Lotman, is “a materially expressed substitution for objects, phenomena, and concepts in the process of information exchange in a collective.” 12 In other words, a sign is something that represents the designated object, indicates its presence, and, in some sense, replaces it. An icon, in a way, is such a sign: it points to the presence of Christ and represents His presence in worship and prayer. This is precisely why “the honor given to the icon” “is transferred to its prototype”: the prototype is designated by the image, and the image points to the prototype. But what was the Cross for the early Christians? The answer to this question is found in very early texts dating back to the early to mid-2nd century. Already the “Epistle of Barnabas” (written, as is known, no later than 130-132 AD) says that the Cross “has grace”: “The cross, similar to the letter ‘tau,’ will have grace.” (σταυρὸς ἐν τῷ ταῦ ἤμελλεν ἔχειν τὴν χάριν).13 Why? Because, as St. Justin the Philosopher points out in his Apology (153 AD), “the Cross, as the prophet predicted, is the greatest symbol of Christ’s power and authority.”14 The Cross has grace as a symbol indicating the presence of Christ’s power and authority. Of course, Christ’s power and authority cannot be thought of separately from Christ Himself, and therefore the Cross is a sign of the Crucified Christ, His representation, an indication of His presence. This is precisely why the Apostle Paul, who urged “let the one who boasts, boast in the Lord” (1 Cor. 1:31), at the same time emphasized that he “does not wish to boast except in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ” (Gal. 6:14). To boast in the Cross and to boast in Christ meant the same thing for the Apostle. The Cross was a sign of Christ.

An additional confirmation of this thought can be served by the fact that the first known image of the Cross is not just the sign of the Cross but the so-called “staurogram.” The staurogram (⳨) is present in some of the earliest papyri of the New Testament in the word “cross” (σταυρός).15 It was common practice for scribes to use special abbreviations for writing sacred names (nomina sacra): “Lord” (κύριος), “Christ” (Χριστός), “God” (θεός), “Jesus” (Ἰησοῦς), and, actually, “cross” (σταυρός). Typically, words were shortened to the first and last letters (κς, χς); a line was drawn over the letters. The task, of course, was not to save time and effort for the scribe but to express reverence for those entities designated with nomina sacra. However, when the word σταυρός was used in terms of nomen sacrum, it was not shortened to two letters — instead, a staurogram was used (C⳨ΟC). The symbol (⳨) consists of two Greek letters, “tau” (Τ) and “rho” (Ρ), but what is important here, as researchers note, is the resulting image. The staurogram is a kind of stick figure drawing, visually representing a person hanging on the cross. The closed loop at the top is his head. As noted by L. Hurtado, a professor at the University of Edinburgh, “this means that historians of early Christian art should revise the conventional notions about when we can date the earliest visual mentions of the crucified Jesus.”16 It should be noted that writing the names “Jesus” and “Christ” as nomina sacra alongside “Lord” and “God” is perceived by researchers as a sign that the divinity of Christ the Savior17 was recognized in early Christianity; but if this is the case, then the writing of σταυρός as a “nomen sacrum” allows us to speak of the veneration of the Cross as a sacred sign, as a “sign of Christ.”

IV. The Cross in Worship and Prayer

It would seem, in light of what has been discussed above, our initial thesis can be considered quite plausible: by the 2nd-3rd centuries, the Cross had indeed become a “sacred image.” It represented Christ and served as His sign. Because of this, we can also speak of the Cross’s “veneration,” of sorts as evidenced by the writing of the word σταυρός alongside the words θεός, κύριος, or Χριστός as nomen sacrum. However, an icon is not just a sacred and venerated image; it is an image used in prayer, worship, and personal piety. Did the Cross figure in the spiritual life of early Christians in this capacity? The evidence of the Cross’s use in prayer can be divided into two categories: testimonies about the sign of the Cross and testimonies about the veneration of the Cross itself.

i. The Sign of the Cross. At first glance, it is not entirely obvious how the sign of the Cross is related to the veneration of sacred images, but as we believe, an examination of the available evidence will help us understand why we consider these issues related.

The earliest Latin testimony about the sign of the Cross comes from Tertullian and is found in his treatise “De corona” (208-212 AD):

“At every forward step and movement, at every going in and out, when we put on our clothes and shoes, when we bathe, when we sit at the table, when we light the lamps, on couch, on seat, in all the ordinary actions of daily life, we trace upon the forehead the sign (signaculo).”18

Origen, in a similar manner, reports this practice in the first half of the 3rd century, citing an earlier author whose works have not survived:

“And a certain third one, among those who believed in Christ, said that among the ancient writings there was the letter ‘tau,’ which has the likeness of the sign of the Cross (τοῦ σταυροῦ χαρακτῆρι), so that this is a prophecy of the sign, which is made on the forehead of Christians. All who have believed make it when they begin any work, especially before prayer or sacred readings.”19

In other words, by the beginning of the 3rd century, during the time of Tertullian and Origen, the sign of the Cross was already not a new and well-established custom. It was not new for the author referred to by Origen. The history of the sign of the Cross goes back to the depths of the 2nd century AD, in direct proximity to the apostolic era.

What significance did early Christians attach to the sign of the Cross? This is clearly stated in the liturgical text of the early Church — the so-called “Apostolic Tradition” (formerly mistakenly attributed to St. Hippolytus of Rome). The instruction on the sign of the Cross contained in this book, according to researchers, belongs to the 3rd century:

“But imitate him always, by signing thy forehead sincerely; for this is the sign of his Passion, manifest and approved against the devil if so thou makest it from faith; not that thou mayest appear to men, but knowingly offering it as a shield. For the adversary, seeing its power coming from the heart, that a man displays the publicly formed image of baptism, is put to flight.”20

Thus, the sign of the Cross is a “sign against the devil.” The depiction of the Cross by hand on the forehead, according to early Christians, had an apotropaic function — it could drive away demons. In other words, through the depiction of the Cross, the power of Christ manifested itself (demons can obviously only be expelled by the power of God). The Cross not only pointed to Christ but also represented Him; demons paid the same honor to the depicted Cross as they did to God — before God demons “believe and tremble” (James 2:19), and from the Cross, they fled trembling. Christians of the 2nd-3rd centuries depicted the Cross on their foreheads, hoping thereby to partake in the power of Christ and drive away demons. All this means that:

a. The depiction of the Cross was sacred to them, and they venerated it,

b. They thus gave honor to Christ and believed that by doing so, they were partaking in Christ.

ii. Veneration of the Cross as an Object:

One of the earliest testimonies of the veneration of the Cross as a wooden object can be found in Tertullian’s apology “Ad Nationes” (after 197 AD):

“And whoever calls us ministers of the Cross (crucis antistites), he will be our fellow minister (consacerdos). What is the distinguishing feature of the Cross (crucis qualitas)? It is a sign made of wood. And what you venerate (colitis) is made of wood, to which the features of an image are given. Only you have the wood in the form of a man, and we have it in its own form. And what now about the outlines, when the distinguishing feature is the same? Why does the form matter if the body of God is the same (dei corpus ipsum sit)? But if from this arises a difference, then what will distinguish the Attic Pallas or the Egyptian Ceres from the longitudinal part of the Cross, which is depicted without form, an unprocessed pole, simply an idol of unprocessed wood? Yes, any log set upright is already part of the Cross, and indeed the greater part! But we are blamed for having a whole Cross, that is, with a crossbeam and a protrusion for support (sedilis excessu). So you deserve more blame for deifying a mutilated stump, while others consider the whole tree to be sacred (consecrauerunt) and [correctly] arranged.”21

Thus, Christians “consider sacred” the wood of the Cross; they are “ministers of the Cross” — an accusation Tertullian does not deny! Given what we already know about Christians’ attitude toward the Cross, this should not be surprising. After all, if they surrounded the cross drawn with a finger on the forehead with such reverence, shouldn’t the veneration of the wooden Cross be greater?

___

Christians in the early 3rd century considered wooden depictions of the Cross sacred.

____

Another testimony of Christians’ veneration of the Cross we encounter again in a polemical context. “The Book of John” is a sacred scripture of the Gnostic ethno-religion of the Mandaeans, a community whose presence in Mesopotamia is recorded from the 3rd century — and this book contains a criticism of Christians’ veneration of the Cross:

“They nail the Cross to the wall, then rise and bow to the wooden object. Let me warn you, my brothers, against a God made by a carpenter.”22

This description helps us better understand why Christians were considered “ministers of the Cross” by Tertullian’s opponents — they literally worshiped before this wooden depiction. This practice existed in the beginning of the 3rd century, and possibly earlier (if by Tertullian’s time the criticism on this matter had already gained widespread attention). But what was the theology behind this veneration?

In the Syriac “Martyrdom of Saints Hyperichius (Hipparchus), Philotheus, James, Habib (Habbib), Julian (Lollian), Romanus, and Parigorius (Paragra),” who suffered in 307-308 AD, it is narrated:

“In the house of this Hipparchus, they had a well-established locked room. On its eastern wall, they depicted a Cross. In this room, they worshiped the Lord Jesus Christ seven times a day before the image of the Cross, turning their faces to the East… When Hipparchus and Philotheus affirmed that in this way they worshiped the Almighty Creator of the world, James asked, ‘Do you really consider this wooden Cross to be the Creator of the world? For we see that you serve it.’ Hipparchus [replied] to him, ‘We worship the One who hung on the Cross.'”23

Although the Martyrdom was “most likely compiled by an eyewitness,”24 it contains traces of revisions carried out in the period after the Nicene Council (the words of the Nicene Creed are placed in the mouths of the martyrs). Nevertheless, the veneration of the Cross occupies an important place in the event series of the Martyrdom, so the report of the existence of an image of the Cross and the worship before it can be considered quite authentic and related to the pre-Constantinian era.25 The theological justification given for the practice of worship before the Cross coincides with the theology of the icon of the Seventh Ecumenical Council: the martyrs worship Christ before the Cross, that is, honor which is given to the Cross as the image of the Saviour’s sacrifice refers to the “hypostasis of the Depicted One.” A similar testimony is found in the “History of John, the Son of Zebedee,” a Syriac apocryphon of the late 4th-5th century:

“And when they fell silent, St. John jumped up, stood, and made them a sign with his hand to be silent; and he took out the Cross, which was on his neck, and looked at it, and applied it to his eyes, and kissed it. Then he wept and stretched out his right hand and made the sign of the Cross over the whole assembly and placed the Cross on the highest row of seats, which was the most eastern of all, and set lights before it.

And they cried out with a loud voice and said, ‘O servant of Jesus, explain to us what you have done with us.’ And the saint gave them a sign, and they fell silent; and he began to speak and said, ‘Beloved children, whom the Gospel has conquered! This is the Cross of the Son of God, eternally abiding with His Father. He created these heavens and these stars placed in the heavens, and all His creations depend on Him. And I made this Cross a bulwark for you so that Satan could not come, gather his demons, and instill in you sleep or carelessness of mind.’ And they exclaimed, ‘For us, this night is day, for now, life has come to us.’ And they comforted each other.

And when they fell silent, all the people ran; and when they ran, they turned their backs to the west and fell down before the Cross, turning to the East, and wept, and said, ‘We worship You, Son of God, hung on the tree.’ And the procurator lay prostrate before the Cross.”26

Despite the relatively late origin of the composition, the majority of the statements we observe here are already known to us from texts we have quoted above: worship before the Cross, the Cross as protection from the devil, making the sign of the Cross to protect against demonic temptations. To worship the Cross means to worshiping Crucified Christ — this thought we encountered in the account of the martyrs of Samosata.

___

“…they fell down before the Cross, turning to the East, and wept, saying, ‘We worship You, Son of God, hung on the tree’…”

___

Let us try to summarize what has been said about the Cross. For Christians of the 2nd and 3rd centuries, the Cross was a sacred image, a sign of Christ’s power, pointing to Christ Himself. The Cross and the sign of the Cross “had grace”; through them, according to the saints of that era, the power of God acted, expelling demons. This set of ideas already implies icon veneration and contains it as a necessary consequence. But in the 3rd century, it seems that the veneration of the Cross appeared in the direct, “iconic” sense — they worshiped before the image of the Cross, perceiving this worship as worship of Christ Himself, whom this sacred sign represented. This can be considered the beginning of explicit icon veneration.

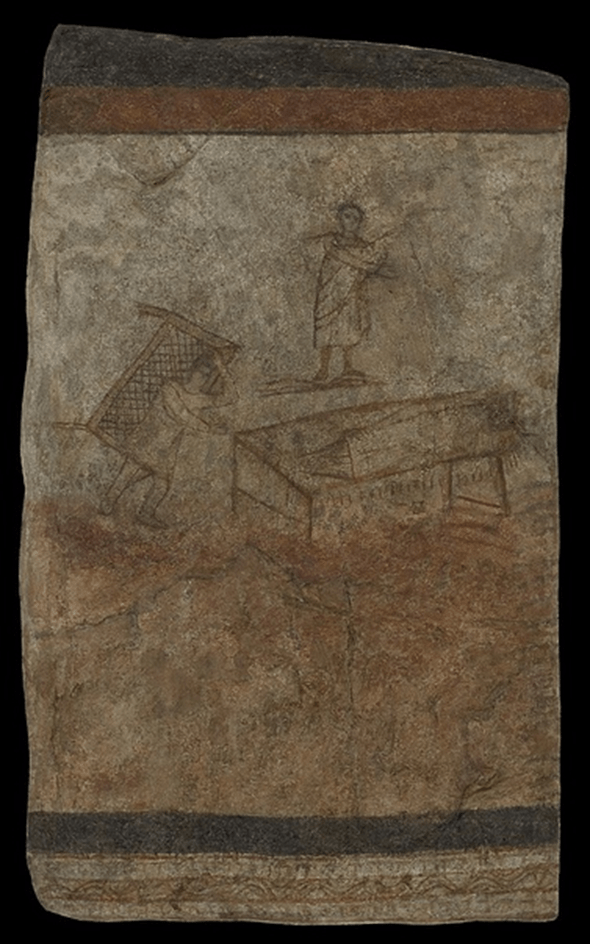

V. Other Sacred Images in the Pre-Nicene Period

Even the most stubborn opponent of icon veneration cannot deny that early Christianity was not iconoclastic. Already at the beginning of the 3rd century, frescoes with depictions of Christ in the symbolic image of the Good Shepherd are featured in the catacombs, as well as the Mother of God with the Child. Moreover, in the famous church at Dura-Europos (233-256 AD), there are already frescoes with directly biblical scenes: Christ saving the drowning Peter, healing the paralytic; probably there is also a depiction of the Annunciation.27 Both symbolic and biblical images existed and were familiar to early Christians. The radical aniconism, evidence of which we find in the texts of some ancient authors (which we will discuss below), did not reflect the reality of the life of the ancient Church at least from the beginning of the 3rd century.

However, our opponents do not deny the very fact that early Christians had images of the sacred. They simply deny that these images were sacred and that they were objects of veneration. Using the example of the Cross and the sign of the Cross, we have shown that even here, the opponent is mistaken: such veneration existed. But can we speak of the veneration of any other images?

The first evidence that suggests that early Christians might have had sacred images (specifically, might have had them — such indirect evidence does not provide strict results) — are critical testimonies, coming, however, from unorthodox authors. The “Acts of John,” written under significant Gnostic influence (dated to the mid-2nd century), includes the following episode:

“And a large crowd gathered because of John. And while he was conversing with those present, Lycymedes, who had a friend — a talented painter, ran to him and said, ‘You see, I have come to you myself. Go quickly to my house, and whom I show you, paint him so that he does not know.’ The artist, having handed someone the tools and paints he needed, said to Lycymedes, ‘Show me him, and don’t worry about the rest.’ And Lycymedes, showing John to the artist, brought him closer and, closing him in one of the rooms from which the apostle of Christ was visible, himself remained with the blessed one, enjoying faith and knowledge of our God. And he rejoiced most of all because he would have him on a portrait.

So the artist, making a sketch on the first day, departed. And on the next day, he colored it with wax paints and thus gave the portrait to the joyful Lycymedes. Having placed it in his room, he adorned it with a wreath so that later John, having realized, said to him: ‘My beloved child, what are you doing, coming from the bathhouse to your room alone? Am I not praying with you and other brothers? Or are you hiding from us?’ Saying this and joking with him, he enters the room and sees the portrait of the elder adorned with a wreath, with lamps on its sides, and altars in front of it. And calling him, he said: ‘Lycymedes, what does this portrait mean to you? Which of your gods is drawn here? For I see that you still live as a pagan.’ Lycymedes answered him: ‘I have one God — the One Who raised me from the dead with my wife. And if, besides God, people — our benefactors — can be called gods, then it is you, depicted in the painting, whom I adorn with a wreath, kiss, and honor as the one who became a good guide for me.’

And John, who had never seen his own face, said to him, ‘You are joking with me, child. Is this what I look like? [In the name of] your Lord, how do you persuade me that this portrait resembles me?’ Then Lycymedes brought him a mirror. And seeing himself in the mirror and looking at the portrait, he said: ‘As my Lord Jesus Christ lives, the portrait resembles me! But not me, child, but my bodily apparition.'”28

Without a doubt, this text contains criticism of the practice of venerating sacred images; at the same time, criticism could not arise had it not been for the existence of the practice. The “Acts of John” had a strong Gnostic tendency. Regarding Christ’s crucifixion, they say: “And it is not the one on the cross who is Me, Whom you now do not see, but only hear the voice. I was thought to be what I am not, for I am not what I am to most; but what they will call Me is lowly and unworthy of Me. Therefore, if the place of rest is invisible and unspeakable, then much more can I, its Master, not be seen, nor spoken of. And the <unequal> mass around the Cross is the lower nature. And those you see on the Cross, since they do not have a single appearance, have not yet gathered all of them — the members of the one who descended.”29 This is an openly Docetic text, denying the reality of the crucifixion and the very incarnation of Christ. Its author implicitly criticizes the veneration of the Cross: “And when Wisdom is in harmony, then there is right and left: powers, authorities, principalities, demons, actions, punishments, rages, slanders, Satan, and the root of the underworld, from which the nature of everything becoming has arisen. So, this Cross, which established everything with the Word and separated everything that has birth, and the lower, and then poured into everything, is not that wooden cross which you will see when you descend from here.”30 Naturally, a Gnostic-Docetist will criticize images of the saints as well. But if he puts in the mouth of the apostle condemnation of such an image and its veneration (veneration with flowers, candles, performing prayer before it), it may mean that such veneration already existed among Christians (as opposed to Gnostic-Docetists).

The second example is somewhat more obvious. In one of his latest writings, written after his conversion to Montanism, Tertullian criticizes the practice of accepting repentant adulterers into church fellowship. The hierarchy of the Catholic Church, which allowed this practice, justified the possibility of such repentance by referring to the book “The Shepherd” by Hermas, and so Tertullian sharply notes:

“I would yield to you if the writings of ‘The Shepherd,’ so favorable to adulterers, were worthy of inclusion in the official lists of the Divine [Scriptures], if by the judgment of any church, including your own, they were not considered apocryphal and spurious. This book itself is adulterous, and therefore defends its kind. It has initiated you into other mysteries. And it is probably that very Shepherd whom you depict on the chalice; and rightly so: for he himself brings forth the Christian Mystery for debauchery, this idol of drunkenness, and refuge for fornication following the chalice.”31

From this reasoning, notwithstanding Tertullian’s rigourism, we learn that the hierarchy of the Catholic Church in the first half of the 3rd century adorned the Eucharistic chalice with an image of the Shepherd. There is no need to guess what they wanted to say: it was an image of Christ in the form of the Good Shepherd. The cup of the Body and Blood of Christ was distinguished from other cups by the image of Christ. And of course, the functions of such an image were not purely ornamental — it was directly included in the most important Christian worship and associated with the Eucharist.

Finally, in the 3rd century, St. Methodius of Olympus speaks directly about the veneration of God through sacred images (images of angels):

“So the images of earthly kings are honored by all, even if they are made not of very precious materials — gold or silver. People, respecting (these images), made of very precious material, do not despise those made of less precious materials, but honor all on earth, even if they are made of plaster or copper. And whoever dared to revile any of them is not released, as one who reviled dirt, and is not judged as one who demeaned gold, but as one who acted impiously against the King and Lord Himself. And the images of His Angels (God), Principalities, and Powers, which we arrange in His honor and glory, are made of gold.”32

VI. A Few Words About the Opponents’ Argumentation

1. In several cases, our opponents simply use quotations erroneously. For example, our opponents often cite Book VII of Origen’s “Against Celsus”:

“Celsus says that Christians cannot stand temples, altars, or images… It is impossible to know God and turn with prayers to images simultaneously.”33

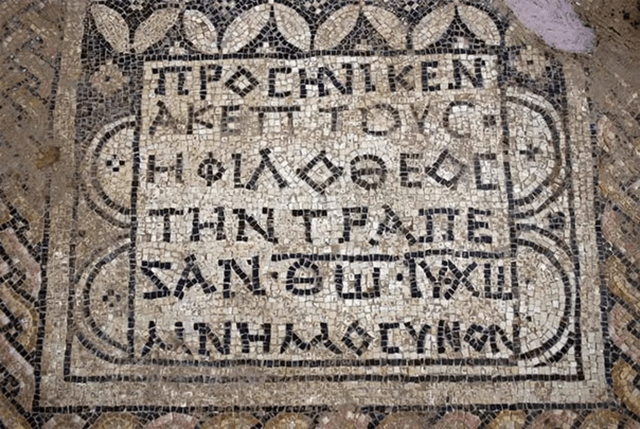

Our opponents refer to the statements of several authors from the early centuries (in particular, Origen, Arnobius, and Minucius Felix), who claimed that Christians had “neither temples, nor altars, nor images, nor incense.” However, we know quite definitively that in the 3rd century, when many of these authors were writing, Christians did have temples and altars. In fact, the two oldest surviving Christian temples serve as living evidence that the words of these writers cannot be understood literally.

We’ve already talked about temples — wasn’t the church in Dura-Europos a temple? During the 2005 excavations in Megiddo, a church built in the 30s of the 3rd century and abandoned in 305 AD due to persecution was discovered. In it was found a mosaic reading: “God-loving Akeptus brought this table (τράπεζαν) to God Jesus Christ for commemoration.” The “table” (more precisely, the “holy table” (ἱερὰ τράπεζα) is the Greek name for an altar, on which the Eucharist is celebrated in Orthodox churches. In other words, Akeptus — likely a wealthy person — donated a holy Altar to the church in Megiddo, which was obviously specially decorated; otherwise, there would be no point in bringing it as a gift to the temple and leaving an expensive mosaic inscription about it. For this, they would have commemorated him during the service. Consequently, Christians in the time of Origen had both temples and altars. If Arnobius, Minucius Felix, and Origen were not passing off wishful thinking as reality (i.e., not claiming that Christians had no temples and altars simply because they wanted them not to exist), then we must conclude that we are simply misunderstanding them. Christians did not have temples similar to the pagan ones; Christians did not have altars like pagan ones, with blood sacrifices and animal slaughter. Accordingly, Christians did not have images — meaning only those like pagan ones.

ii. This consideration I closely related to what we’re going to say next. Our opponents provide a series of texts in which early Christian apologists criticize treating images as sacred — but they almost always do so in the context of polemics with paganism. Let’s suppose Clement of Alexandria acts as an aniconist when he writes that “works of art cannot be considered sacred and divine” because “they remain forever lifeless, material, and contain nothing holy.” However, he says so by him in the context of a polemic with the pagan concept of the divine; we do not know and cannot know what Clement would have said about the depiction of the incarnate Christ (we could assume he would have condemned it due to his Platonic inclinations — but only assume).

___

Early Christian apologists criticize the worship of images almost exclusively in the context of polemics with paganism.

___

Our remark is proved reasonable by another fierce aniconist who is present in many of the aniconist florilegia. Tertullian, of course, says that “every picture or painting depicting anything should be considered an idol.”34 But this categorical statement, if understood literally, certainly contradicts the reality of church life at the beginning of the 3rd century — the church in Dura-Europos and the Roman catacombs are full of “pictures and paintings” of various kinds. Was the Roman Christian community entirely idolatrous? The point, however, is that the treatise “On Idolatry,” quoted by many of our opponents, belongs to Tertullian’s “Montanist” works. But in a somewhat earlier work — the treatise “Against Marcion,” the North African apologist reasons a bit more subtly:

“Likewise, when forbidding the similitude to be made of all things which are in heaven, and in earth, and in the waters, He declared also the reasons, as being prohibitory of all material exhibition of a latent idolatry. For He adds: “Thou shalt not bow down to them, nor serve them.” The form, however, of the brazen serpent which the Lord afterwards commanded Moses to make, afforded no pretext for idolatry, but was meant for the cure of those who were plagued with the fiery serpents. I say nothing of what was figured by this cure. Thus, too, the golden Cherubim and Seraphim were purely an ornament in the figured fashion of the ark; adapted to ornamentation for reasons totally remote from all condition of idolatry, on account of which the making a likeness is prohibited; and they are evidently not at variance with this law of prohibition, because they are not found in that form of similitude, in reference to which the prohibition is given” 35[2]

Moreover, in the same chapter, Tertullian reasons that sacrifices condemned by God, when offered to false deities, become virtuous deeds when offered to the true Lord:

“We have spoken of the rational institution of the sacrifices, as calling off their homage from idols to God; and if He afterwards rejected this homage, saying, “To what purpose is the multitude of your sacrifices unto me?” — He meant nothing else than this to be understood, that He had never really required such homage for Himself. For He says, “I will not eat the flesh of bulls; ” and in another passage: “The everlasting God shall neither hunger nor thirst.” Although He had respect to the offerings of Abel, and smelled a sweet savour from the holocaust of Noah, yet what pleasure could He receive from the flesh of sheep, or the odour of burning victims? And yet the simple and God-fearing mind of those who offered what they were receiving from God, both in the way of food and of a sweet smell, was favourably accepted before God, in the sense of respectful homage to God, who did not so much want what was offered, as that which prompted the offering. Suppose now, that some dependant were to offer to a rich man or a king, who was in want of nothing, some very insignificant gift, will the amount and quality of the gift bring dishonour to the rich man and the king; or will the consideration of the homage give them pleasure?” 36

And so, if “Montanist Tertullian” finds it possible to call “any picture” an idol, then in a more sensible period of his activity, he quite clearly states the key consideration — it is not “pictures” that are prohibited but idolatry; not images but the worship of false gods (or material objects as gods). The prohibition does not apply to images made by the will of the true God.

iv. Tertullian’s logic in the book “Against Marcion” corresponds to St. John of Damascus’s reasoning in his apology for icon veneration:

“You must know, Beloved, that in every business truth and falsehood are distinguished, and the object of the doer, whether it be good or bad. In the gospel we find all things good and evil. God, the angels, man, the heavens, the earth, water and fire and air, the sun and moon and stars, light and darkness, Satan and the devils, the serpent and scorpions, death and hell, virtues and vices. And because everything told about them is true, and the object in view is the glory of God and the saints whom He has honoured, our salvation, and the shame of the devil, we worship and embrace and love these utterances, and receive them with our whole heart as we do the whole of the old and new dispensation, and all the spoken testimony of the holy fathers. Now, we reject the evil, abominable writings of heathens and Manicheans, and all other heretics, as containing foolishness and lies, promoting the advantage of Satan and his demons, and giving them pleasure, although they contain the name of God. So with regard to images we must manifest the truth, and take into account the intention of those who make them. If it be in very deed for the glory of God and of His saints to promote goodness, to avoid evil, and save souls, we should receive and honour and worship them as images, and remembrances, likenesses, and the books of the illiterate. We should love and embrace them with hand and heart as reminders of the incarnate God, or His Mother, or of the saints, the participators in the sufferings and the glory of Christ, the conquerors and overthrowers of Satan, and diabolical fraud. If any one should dare to make an image of Almighty God, who is pure Spirit, invisible, uncircumscribed, we reject it as a falsehood. If any one make images for the honour and worship of the Devil and his angels, we abhor them and deliver them to the flames.”37

Indeed, the veneration of the icon of Christ is not idolatry because Christians who venerate this icon do not worship any idols. They do not worship Zeus, Krishna, or Quetzalcoatl. The depiction of the Cross or the Crucifixion is made for Christ’s glory; worshiping before the Crucifixion or the Cross, as the martyrs of Samosata did, the Christian relates his worship not to the wood but to the God-man’s Person, who endured the terrible redemptive suffering for our sins. Such bowing of the head before the Cross by a reverent Christian can be considered sinful only for a legalistic, completely Pharisaic mindset, which considers “pictures” something like ritual impurity, tainting a person regardless of his heart’s disposition and intentions.

___

Veneration of the Icon of Christ is not Idolatry Because Christians who Venerate This Icon do not Worship Any Idols

___

v. Finally, it is necessary to say a few words about our opponents’ criticism of the Seventh Ecumenical Council.

Our opponents often claim that the Iconoclastic Council of Hieria in 754 had almost the entire Byzantine episcopate, because this council consisted of 338 bishops. This is true. However, an Ecumenical Council is not made by the number of Byzantine bishops but by the representation of the Universal Church. The council in Hieria did not represent the opinion of the Universal Church, as it was exclusively a gathering of Byzantine bishops without representatives from Rome or the Christian East: “How is it that this gathering is called Great and Ecumenical, when it was not accepted or agreed upon by the heads of other Churches, but on the contrary, it was anathematized? He did not have as his accomplice in this matter the Pope of Rome of that time, or his deputies, representatives, or his encyclical letter, as required by law from such councils. Neither were the Eastern Patriarchs in agreement with this council: the Alexandrian, the Antiochian, and the Holy City, nor their co-celebrating archpriests.”38

Accusations against the Seventh Ecumenical Council of 787 of “politicization” are frankly ridiculous in the context of such a favorable attitude toward the 754 assembly, where there was no patriarch at all, and Emperor Constantine V completely dominated. Patriarchs of the Iconoclastic era were thus described in the sources: “In these unfortunate days, the impious Anastasius seizes the episcopacy with an impious hand, by military force, not by the decision of God’s piety – and he handed over everything church-related to the royal court.”39 At the very council of 754, the emperor himself led the ordination of the iconoclastic Patriarch Constantine. Here is what the sources say about this: “[The Emperor] took him to the church, not by the will of God and the priests, but by his own malice, and when they both ascended the ambo, the unsanctified Constantine was clothed in the vile diploid and omophorion from the hands of Emperor Constantine… Moreover, the tyrant himself proclaimed ‘Axios!’ Oh, unworthiness! The shield-bearer is the establisher of the priesthood, he is spending time in wars and murders – and he’s the celebrant, he’s unlawfully cohabiting with three wives — and he became the ordainer of priests! Who has ever heard such a thing, or seen, or declared? Truly no one.”40 Can one accuse iconophiles of politicization after this? At least Empress Irene did not clothe the patriarch in sacred garments right in the middle of the temple!

As for the West and the western part of the Church, it was not the western part of the Church that rejected the Seventh Ecumenical Council, but the episcopate of the Frankish kingdom, which was also under the strong influence of political power. The Roman bishop, traditionally representing Latin Christianity at the Ecumenical Councils, was always the first defender of icon veneration, starting from the times of Emperor Leo the Isaurian, and did not reject the Council of 787. The words once spoken by Pope Pelagius about the schismatics who did not accept the Fifth Ecumenical Council are applicable to the Frankish iconoclasts:

“I ask: was there ever, as [the schismatics] themselves think, any ‘patriarch of Histria and Venice’ at any of those Ecumenical (generalibus) Councils that we revere? Or maybe he sent legates? If they cannot show this in any way and have no evidence, let them understand that they themselves are not only not the Universal Church (generalis Ecclesia) but cannot even be called a part of the Universal Church if they are not joined to the members of Christ, reuniting with the Apostolic Sees and freeing themselves from their dry branches.”41

Conclusion

Let’s try to briefly outline the results of our apologetic study.

In our opinion, already in the 2nd century, there can be observed a special reverent attitude toward the Cross as a sign, a symbol of Christ’s power and authority. This perception of the Cross has its support in Sacred Scripture: for the apostle Paul, the Cross appears as a symbol representing Christ and even “replacing” Him in statements.

Already at the beginning of the 3rd century, we find direct evidence of the veneration of the depicted Cross: in the form of the sign of the Cross (i.e., the depiction of the Cross by hand on the forehead of a Christian), the Cross was a sign of Christ’s presence, terrifying to demons, and as a wooden sign, the Cross was “sacred” to Christians. In the environment of Gnostic sects and pagan polemicists, Christians in the 3rd century, apparently, could be subjected to criticism for performing worship before the Cross. At the end of the pre-Nicene era, at the turn of the 3rd-4th centuries, not only is the practice of worshiping the Cross established, but also, probably, its theological justification: worship before the Cross is actually the worship of Christ Crucified. This explanation represents, in fact, a brief outline of future icon veneration.

Actual iconographic images (besides the Cross — although it, in its primary form, was depicted using the “staurogram,” a pictogram of the Crucifixion) appear among Christians no later than the first half of the 3rd century. It is more difficult to speak of the veneration of such images, but it should be noted that early Christian apologists almost exclusively criticize images of false gods.

Icon veneration, as proclaimed by the Seventh Ecumenical Council, is a reverent and pious Christian custom that can only be condemned from the perspective of legalistic ritualism.

- DVS. Vol. 7. P. 293. ↩︎

- Ibid. P. 285 ↩︎

- Gregory of Nyssa, St. Eulogy to the Great Martyr Theodore Tyron // Works of St. Gregory of Nyssa. Moscow, 1871. Part 8. Pp. 201-203.

Alternatively, an English translation can be found here: https://www.johnsanidopoulos.com/2010/02/panegyric-to-great-martyr-theodore-tyro.html ↩︎ - Egeria. Pilgrimage to the Holy Places at the End of the 4th Century // Orthodox Palestinian Collection. St. Petersburg, 1889. Issue 20. P. 127. ↩︎

- Teachings of Addai // Meshcherskaya E. N. The Legend of Abgar—An Early Syrian Literary Monument. Moscow, 1984. P. 186. ↩︎

- Egeria. Pilgrimage to the Holy Places at the End of the 4th Century // Orthodox Palestinian Collection. St. Petersburg, 1889. Issue 20. Pp. 158-159.

Alternatively, an English translation can be found here:https://www.ccel.org/m/mcclure/etheria/etheria.htm ↩︎ - Nicephorus Patriarch. Refutatio, 203 // CCSG. Vol. 33. P. 325–326; Russian translation by D. V. Smirnov: https://virtusetgloria.org/translations/epiph/contr_imag/contr_imag_01.html. ↩︎

- Concilium Nicaenum a. 787. Actio VI // ACO II. Vol. 3 (3). P. 706; Russian translation by D. V. Smirnov: https://virtusetgloria.org/translations/epiph/contr_imag/contr_imag_02.html ↩︎

- “It seems to me that the Bishop of Alexandria, Athanasius, acted more correctly when, as I was told, he required the psalms to be recited with such minimal modulation that it was more like declamation than singing. And yet, I recall the tears I shed to the sounds of church singing when I first found my faith; and although now I am moved not by the singing but by what is sung, as it is sung with clear voices, in melodies that are quite appropriate, I again recognize the great benefit of this established custom. Thus, I waver – enjoyment is dangerous, and the saving influence of singing is proven by experience.” (Augustine the Blessed, St. Confessions, X 33.50. Moscow, 2005. P. 366). ↩︎

- Liber Pontificalis / Ed. L. Duchesne. Rome, 1886. Vol. 1. P. 172. ↩︎

- Ibid. P. 285. ↩︎

- Lotman Yu. M. Semiotics of Cinema and Problems of Cinema Aesthetics. Tallinn, 1973. Pp. 2-3. ↩︎

- Epistula Barnabae // The Apostolic Fathers / Ed. B. D. Ehrman. Cambridge (MA), London, 2003. Vol. 2. P. 44. ↩︎

- Justin the Philosopher, Martyr. First Apology, 55 // Works. Moscow, 1995. P. 86. ↩︎

- Bodmer Papyrus 75, beginning of the 3rd century, in particular. ↩︎

- Hurtado L. Earliest Christian Graphic Symbols and Earliest Textual References to Christian Symbols // Texts and Artefacts: Selected Essays on Textual Criticism and Early Christian Manuscripts. London, 2017. P. 94. ↩︎

- Hurtado L. The Origin of the Nomina Sacra // Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity. Grand Rapids (MI), 2003. Pp. 625-627. ↩︎

- Tertullianus. De Corona, 3 // PL. 2. Col. 80. ↩︎

- Origenes. Selecta in Ezech., 9 // PG. 13. Col. 801. ↩︎

- Apostolic Tradition, 42 // Bradshaw P. F. Apostolic Tradition: A New Commentary. Collegeville (MN), 2023. P. 114; see also the introduction to the publication.

Alternatively, an English translation can be found here: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/61614/61614-h/61614-h.htm ↩︎ - Tertullianus. Ad Nationes, I 11-12 // PL. 1. Col. 577-578. ↩︎

- Lidzbarski M. Das Johannesbuch der Mandäer. Giessen, 1915. Vol. 2. P. 108. ↩︎

- Acta Martyrum Samosatae // Assemani S. Acta Sanctorum Martyrum Occidentalium et Orientalium. Rome, 1748. Vol. 2. P. 125. ↩︎

- Duval R. Syriac Literature. Piscataway, 2013. P. 101. ↩︎

- Peterson E. Das Kreuz und das Gebet nach Osten // Frühkirche, Judentum und Gnosis: Studien und Untersuchungen. Freiburg, 1959. Pp. 15-16. ↩︎

- The History of John, the Son of Zebedee // Wright W. Apocryphal Acts of the Apostles. London, 1871. Vol. 2. P. 32. ↩︎

- Serra D. E. The Baptistery at Dura-Europos: The Wall Paintings in the Context of Syrian Baptismal Theology // Ephemerides Liturgicae. 2006. Vol. 120. P. 67. ↩︎

- Vinogradov A. Yu. Apocryphal “Acts of John”. Part I // Bible and Christian Antiquity. 2020. No. 1 (5). Pp. 75-76. ↩︎

- Ibid. P. 91. ↩︎

- Ibid. Pp. 90-91. ↩︎

- Tertullianus. De Pudicitia, 10 // PL. 2. Col. 1000. ↩︎

- Methodius of Olympus, Hieromartyr. On Free Will // Works of St. Gregory the Wonderworker and St. Methodius, Bishop and Martyr. Moscow, 1996. P. 271 (2nd page). ↩︎

- The translation cited by the opponent can be found here: https://www.tertullian.org/russian/de_spectaculis_rus.htm. ↩︎

- Tertullian. On Idolatry, 3. Selected Works. Moscow, 1994. P. 251. ↩︎

- Tertullian. Against Marcion, II 22. St. Petersburg, 2010. P. 172.

Alternatively, an English translation can be found here: [1] https://www.tertullian.org/anf/anf03/anf03-29.htm ↩︎ - Ibid. Pp. 172-173.

English translation: https://www.tertullian.org/anf/anf03/anf03-29.htm ↩︎ - John of Damascus, St. Three Defensive Words Against Those Who Criticize the Holy Icons, I 25. St. Petersburg, 1893. Pp. 21-22.

Alternatively, an English translation can be found here: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/49917/49917-h/49917-h.html ↩︎ - Seventh Ecumenical Council. Act VI // DVS. Vol. 7. P. 208. ↩︎

- Vita Stephani Iunioris // PG. 100. Col. 1085. ↩︎

- Vita Stephani Iunioris // PG. 100. Col. 1112. ↩︎

- Pelagius I Pope. Epistula 24, to John, the patrician caburtario // Pelagii I Papae epistulae quae supersunt. Montserrat, 1956. Pp. 73-74. ↩︎